Body, Temple with Philip-Daniel Ducasse

Photographer Philip-Daniel Ducasse, a former nutritionist and personal trainer, grants us a first look at his new series on fitness enthusiasts in Ghana, and discusses his philosophies of the body.

This story appears in Justsmile Issue 6, Eyes on the Prize.

Photography Philip-Daniel Ducasse

Text Jonathan Jayasinghe

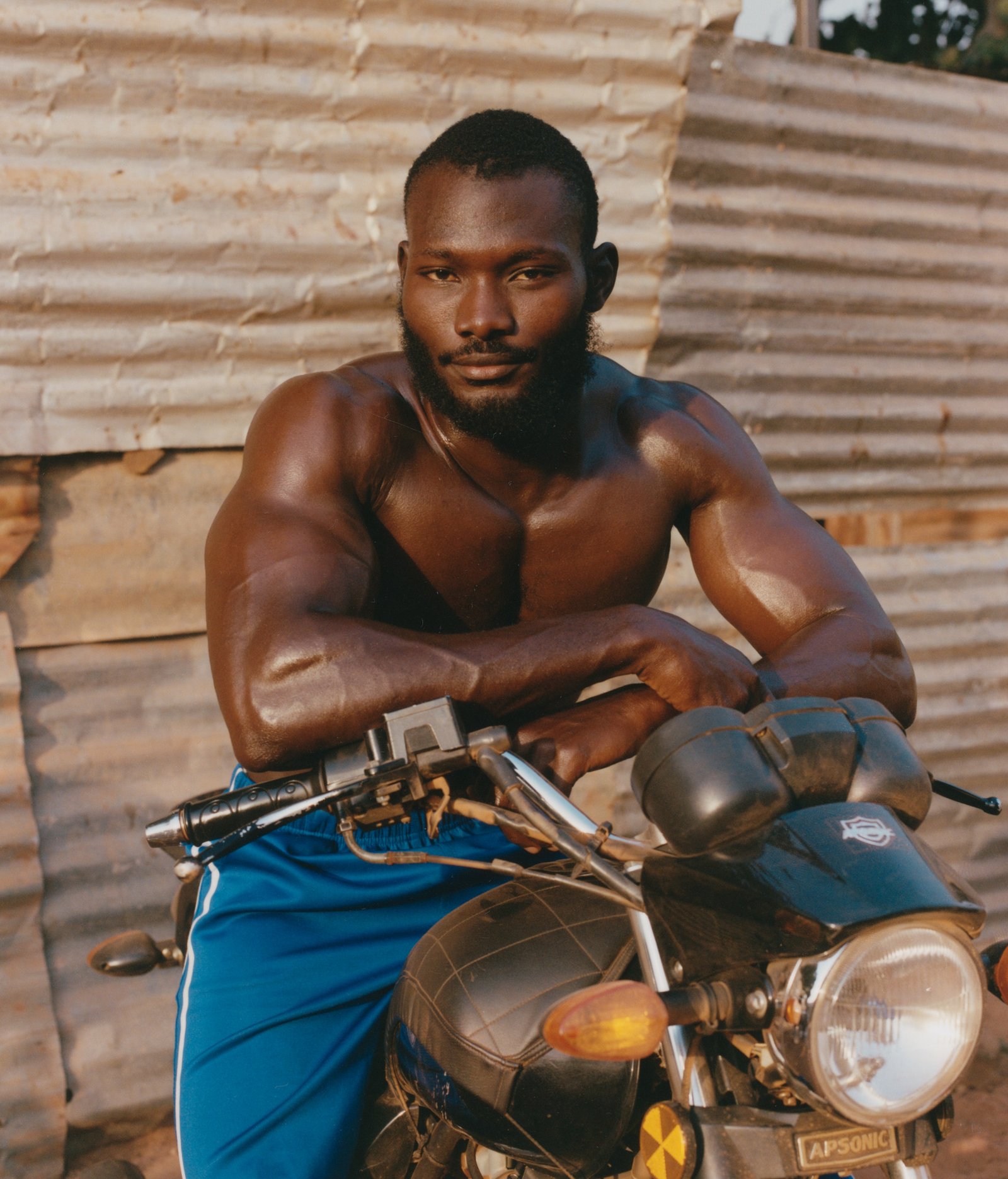

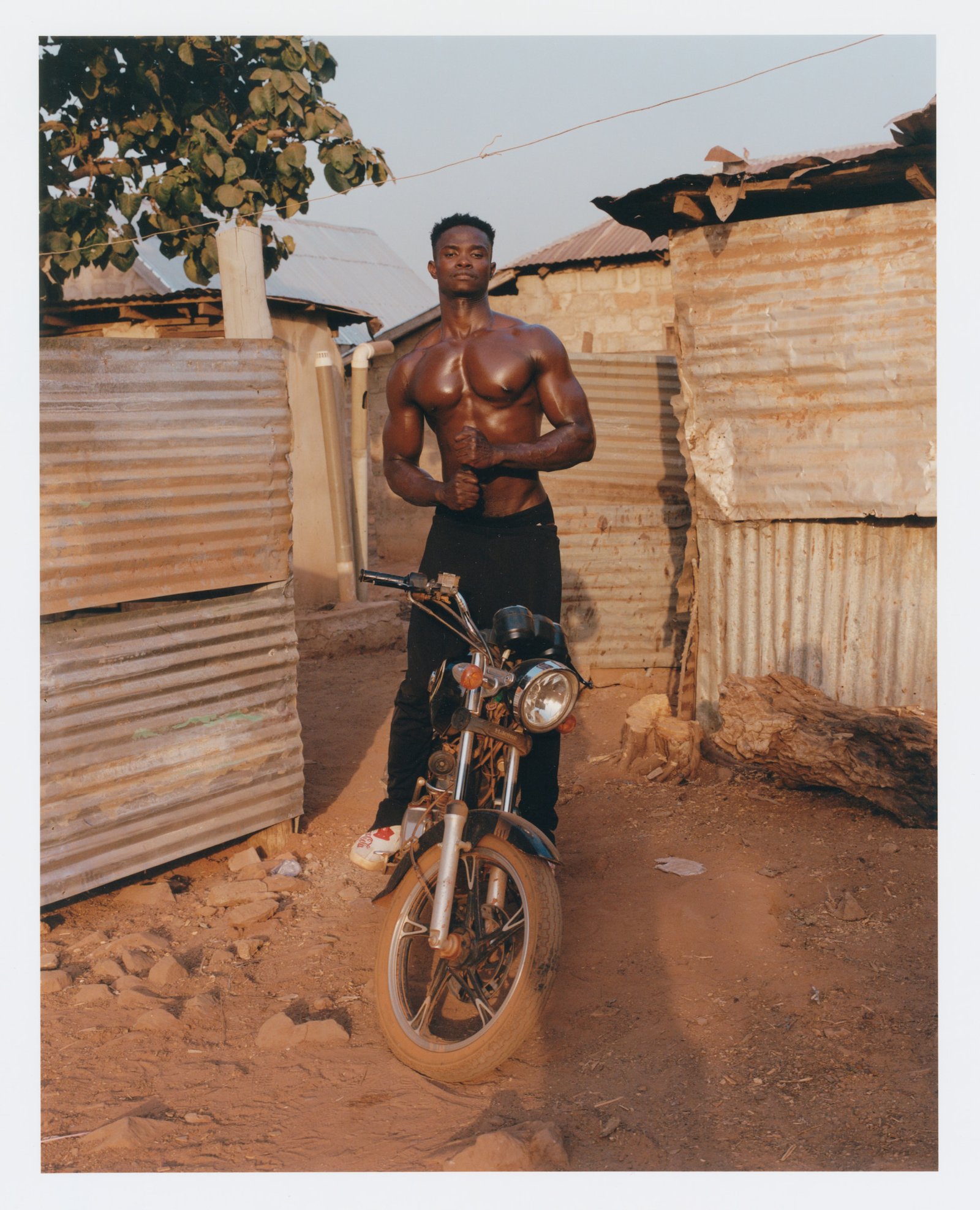

Bodybuilder Iliasu Alhassan, photographed by Philip-Daniel Ducasse

The idea of preservation runs through much of the photographer Philip-Daniel Ducasse’s work. As a child, he would spend hours poring over his mother’s photo albums, sifting through her memories and making them his own. She had him later in life, and those photographs offered backstage glimpses of the person she was before he knew her—a version of her that no longer exists and can’t be fully recovered. These early encounters with images of his mother and other family members shaped a perspective that sees photography as a tool of preservation: of past selves, of cultural and familial histories, of elusive, ephemeral moments in time. “That’s how I really got into photography,” he tells me, one evening in late March. “It was seeing someone you know in a different time. A version of them you missed. That made an impression.”

“That’s how I really got into photography... it was seeing someone you know in a different time. A version of them you missed.”

Ducasse was born in Quebec, but he was raised in Port-au-Prince, where his mother is from. He has since settled in New York City, but Ducasse’s early life was at least partially characterized by intermittent displacement: He left behind his life in Canada to move to Haiti with his family, then left Haiti for Florida when he was 13, and stayed there until he graduated from Florida State University, at which point he, like many artists, he travelled east. This constant migration, this long arc of movement, informs his aliveness to the fleeting and the temporary.

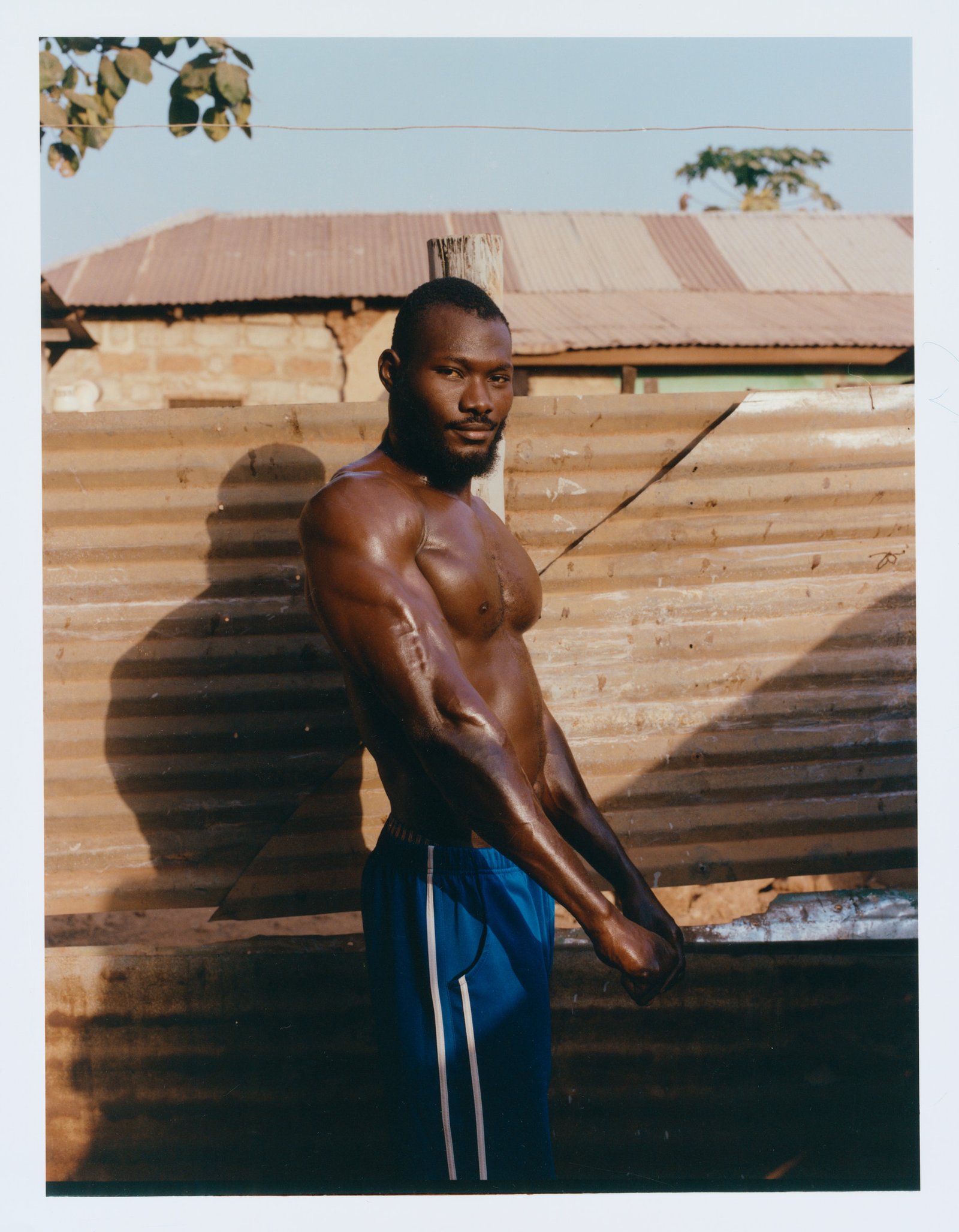

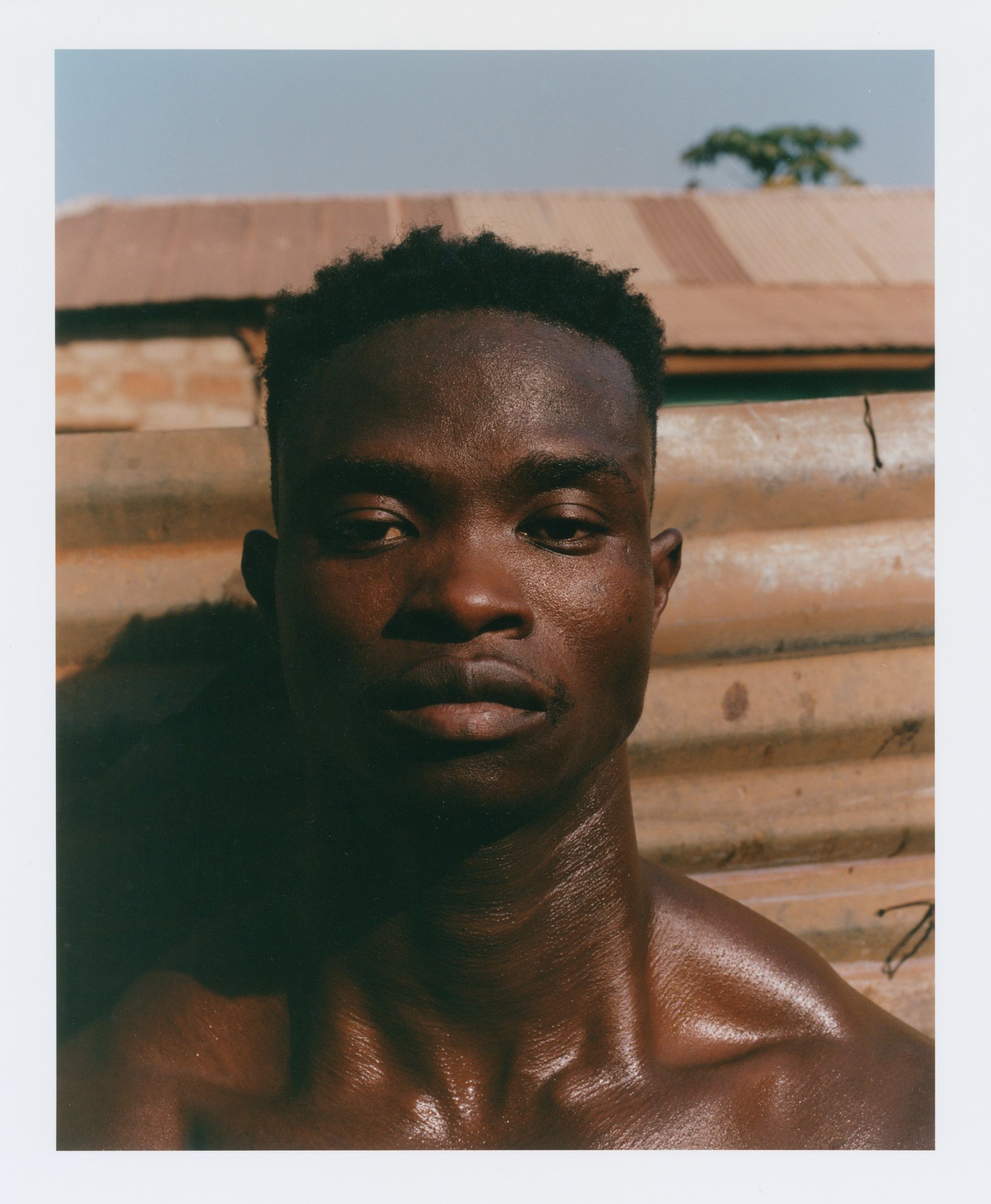

Bodybuilder, Iliasu Alhassan

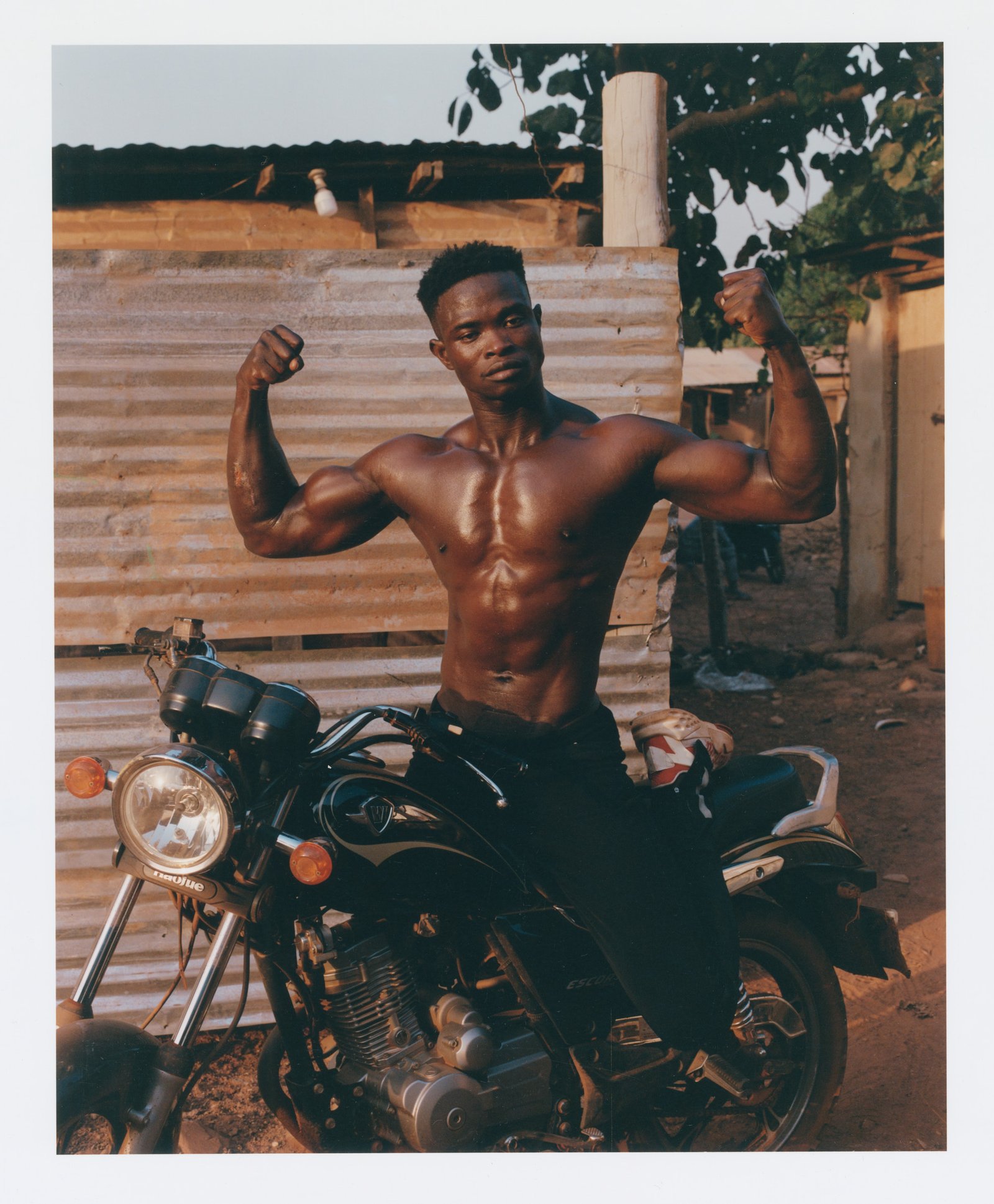

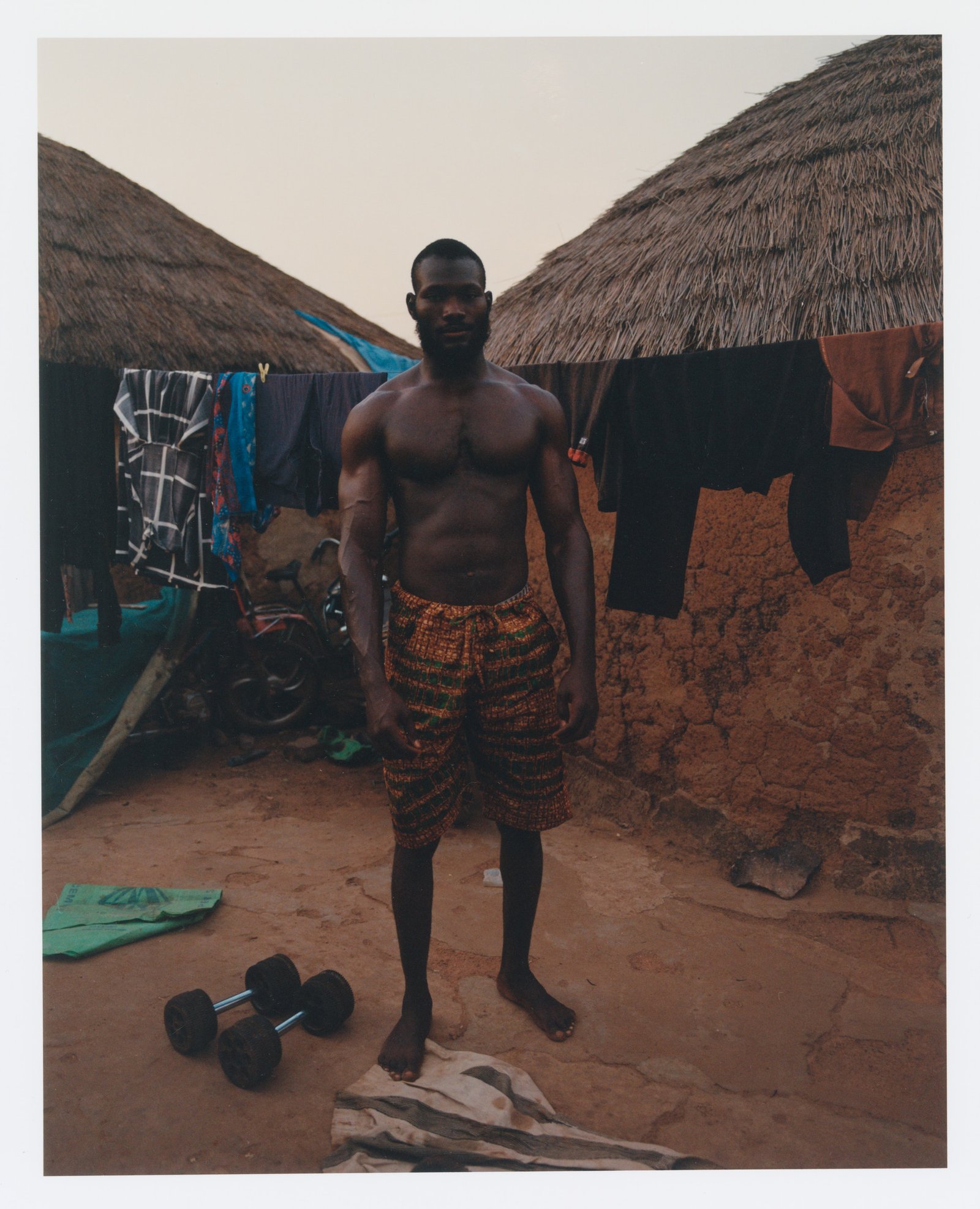

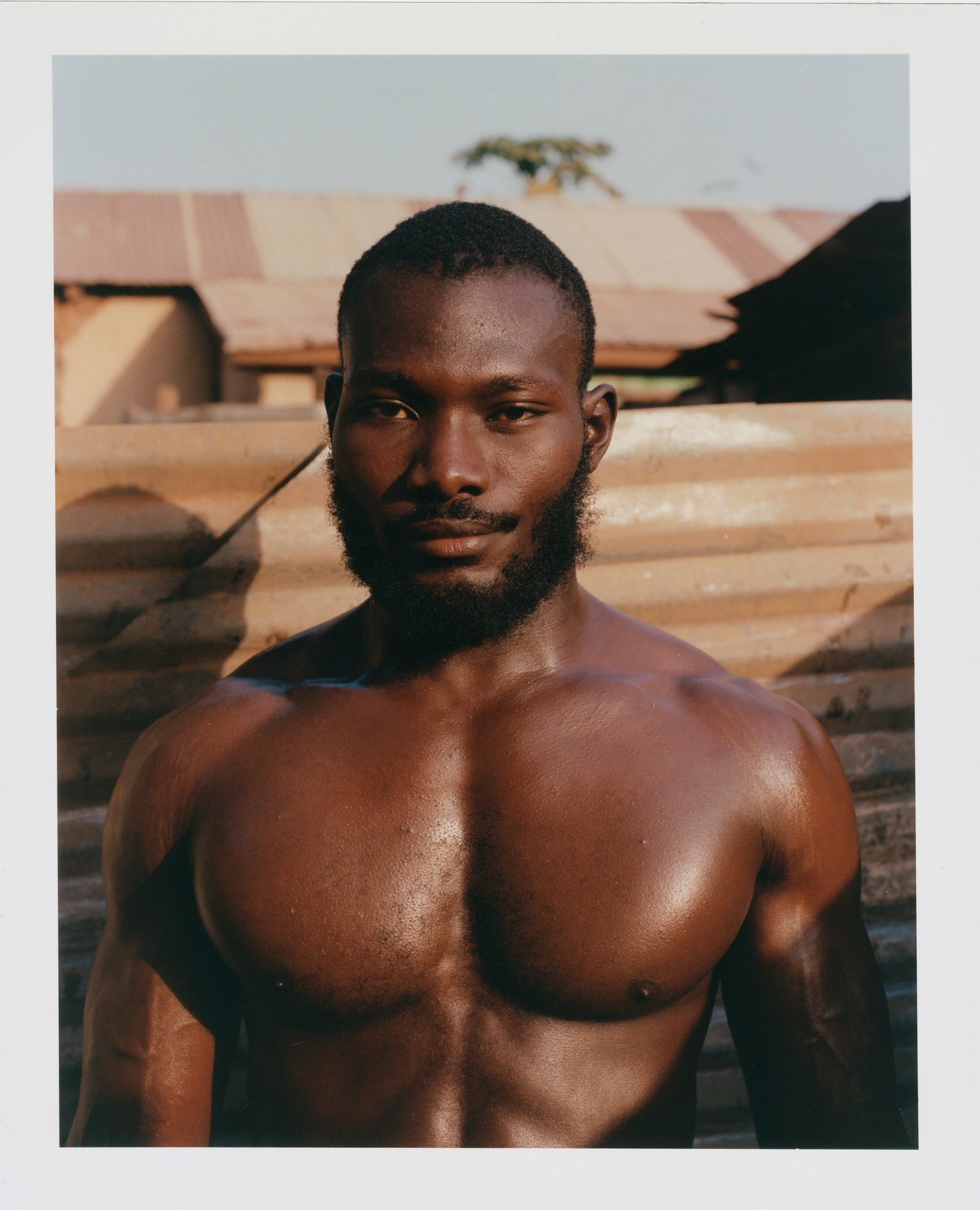

Bodybuilder, Oduro Acheampong

Like many children of the diaspora, Ducasse was raised with narrow expectations for what sort of occupation he might pursue as an adult: doctor, lawyer, or engineer, but never anything so lofty as “artist.” As many of us do, Ducasse did initially pursue a path in line with those expectations, studying pre-med until his junior year of college, where a hospital internship clarified for him that he might not be on his preferred path. He dutifully completed his degree, switching his major to nutrition, before moving to New York to become a personal trainer. With his flexible schedule, he initially pursued his interest in photography and film by spending time on a fashion photographer friend’s sets, shooting films and soaking up everything he could about process and technique.

Ducasse’s early attempts at getting his own editorials published proved unfruitful, and so he chose to take a different approach. Frustrated with the limits of commercial and editorial photography, he began self-assigning projects, pursuing his own subject matter outside of the constraints of the fashion industry. Often, these series evinced a deep fascination with bodies ensnared in varied, spirited social customs: festival-goers in New York, fire breathers in Ghana. The first of these was a series of portraits of the Red Devils, a collective of pantsula dancers in South Africa. While pantsula is a high-energy dance form that emerged in response to the injustice of the apartheid era, Ducasse’s images instead capture the dancers in moments of repose and camaraderie. In a mix of playful solo portraits and group shots that revel in the collective’s bonhomie, Ducasse avoids explicit social commentary and resists commodifying the dynamism of the dancers’ practice. He elects to lean into the connection and self-possession that emerges naturally from engagement with cultural rituals, and the implicit ethnographic histories within.

This approach extends throughout his oeuvre, from personal work to editorial work for a range of fashion publications, campaign work for brands, and photojournalism. Of the latter, his 2024 Curbed story stands out. Ducasse was assigned to photograph migrants waiting outside of a reticketing center at St. Brigid’s Church in New York. He spent three days documenting the line, using his fluency in French and Creole to speak with many of the people who became his subjects. “A lot of them didn’t want to be photographed [due to their legal status],” he says. “They were concerned, but I could relate. I’m an immigrant, too.” The images from that assignment are quietly expressive: elegant portraits of individuals from all over the world—Guinea, Ecuador, Mauritania, Afghanistan—framed against a small white backdrop staged within the space, with minimal adornment or stylization. There’s no attempt to dramatize the conditions or soften the context. At the same time, the tone is gentle. What the images offer in lieu of dreamy fashion scenes or conceptual experimentation is clarity and humanity, a record of presence and dignity amid deeply challenging circumstances. The images take on a new significance amid our current political atmosphere, with an administration that openly targets immigrants and brutally weaponizes the US immigration system.

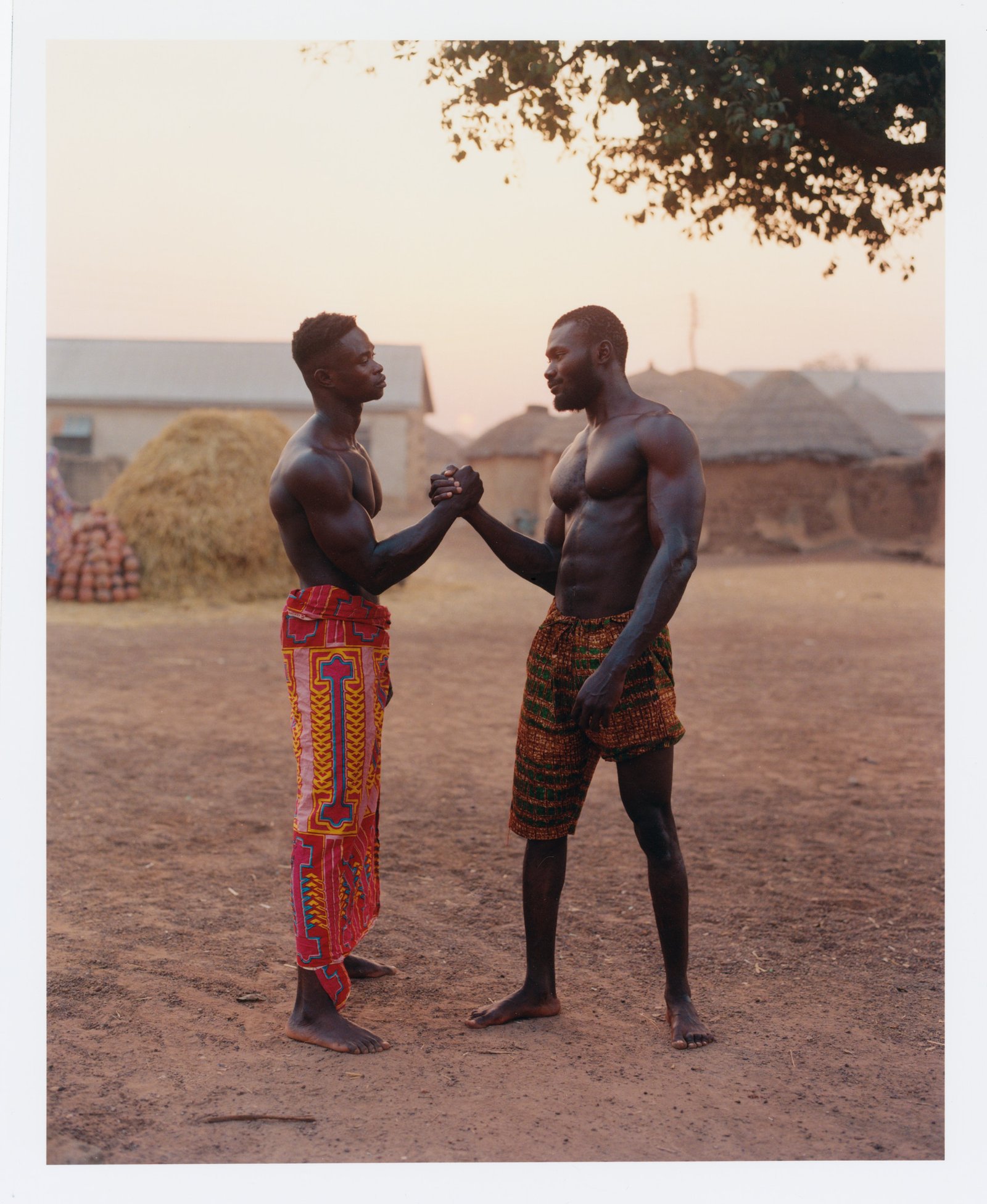

Ducasse’s latest body of work, “Muscle Memory of a Place,” takes a similarly sensitive eye (but with a slightly stylized approach) to a community of fitness enthusiasts in Tamale, Ghana. Composed of a striking series of images and a short documentary film, the project emerged organically during a trip to the region to visit a friend. The images frame his subjects, a pair of local men, in tender portraits within and around their outdoor gym. One of them, Oduro Acheampong, is a fitness model with a large online following, who Ducasse stumbled upon while scrolling Instagram. Oduro became his primary point of contact in Tamale, posing for the series as well as helping to coordinate the shoot itself. In the images, he and another local bodybuilder, Iliasu, are posed casually, exhibiting their immaculately toned physiques as the golden-hour light dissipates around them. Equally striking as the men’s physiques is the gym, handmade by locals from repurposed industrial materials. The functional, rough-hewn space stands in parallel and contrast to the traditional adobe dwellings with thatched roofs featured in many of the images, testaments to material ingenuity and devoted craft.

In this series, Ducasse’s focus on preservation becomes more complex. These are images of bodies at a pinnacle of form, but they do not ignore the temporary nature of that state. He captures these men at their best, but the photographs sit with the fact that this version of the body will shift, that no form holds forever. There is recognition in that framing—not illusion. The strength is earned, but it is also fleeting.

The images in the series are composed with intention but never overly directed. Each frame acknowledges the labor of maintenance: the slow, cumulative effort that builds strength and aesthetic beauty without spectacle. The subjects are not performing for the camera. The result is formal but not rigid, reverent but not overly romantic.

The work avoids documentary classification, but it borrows its sensibility. Ducasse observes rather than directs, and builds intimacy through genuine connection and shared interest. Before making the portraits, Ducasse spent time with the men, working out, discussing nutrition, and building a rapport. He was struck by their eating habits, often only one large meal a day, and the more natural-looking physiques that seemed to emerge from their specific regimens in comparison to the bodies he’s accustomed to seeing in the US. At the same time, the photographs reflect his specific way of seeing. His compositions are marked by clarity and restraint, and deeply responsive to how his subjects hold themselves. His interest in fitness is not commercial or even necessarily aspirational. It lies in relentless devotion to self-improvement and the pursuit of one’s own ideal form.

For Ducasse, photography remains a way of marking what might otherwise go unacknowledged. The gym is not part of a larger system. The men who train there are not widely visible. The tools they use are often unstable or incomplete. But within that space, there’s structure and commitment. By holding that in the frame, the images offer a kind of record. Not of transformation, but of continuity. Preservation, in this case, becomes less about freezing the ideal and more about paying attention to what people create for themselves when no one is looking.

“It’s more about celebrating them and their bodies,” he says. “I just wanted to immortalize that. Because beauty fades.”