Acts of Faith with Emmanuel L. Desir

Ahead of his solo show at Canal 47, titled Let my people go, Emmanuel Louisnard Desir discusses his multivalent uses of bronze, the differences between New York and LA, and the body as a machine.

This story appears in Justsmile Issue 6, Eyes on the Prize.

Photography Chad Unger

Text Maya Kotomori

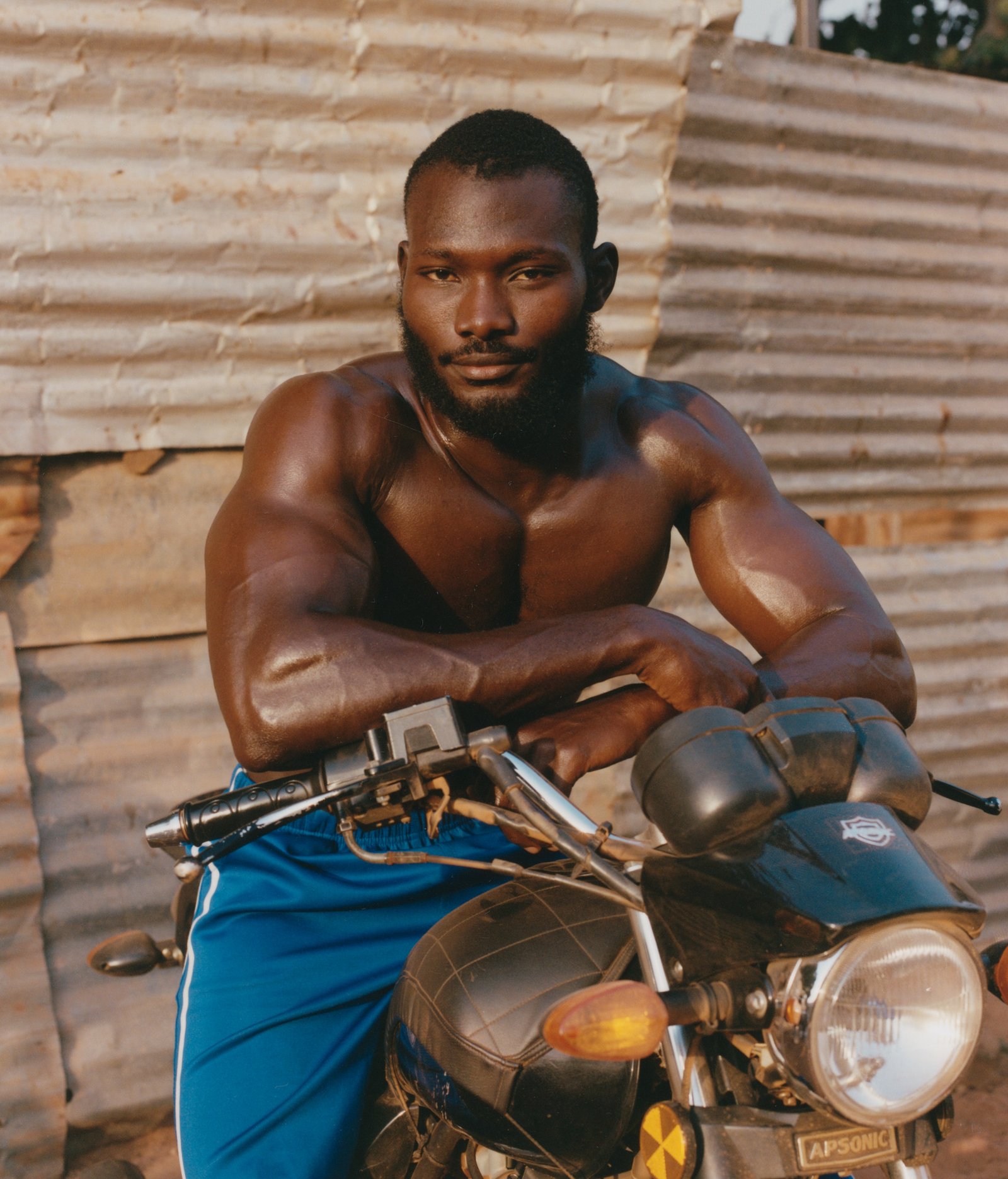

Desir at his studio in Los Angeles.

The wooden woman pleads, her right arm raised to signal her need. A patterned red scarf wraps her head, the dark flat of her face deep in its expressionlessness—her breasts are low, her stomach round, posture hunched. She is Mama U Tried (2019), a sculpture by fine artist Emmanuel Louisnord Desir, a master at freezing animus in his inanimate sculptures.

Brooklyn-born and now Los Angeles-based, Desir quickly made a name for himself in the contemporary art world. His early fascination with creative expression was shaped by his family—drawing inspiration from his father’s “jack-of-all-trades” pursuits in oil painting, and emulating his older brother’s sketches of Yu-Gi-Oh! characters—and his relationship to God. What began as earnest exploration led him to the Cooper Union in New York, where he honed his craft in painting and sculpting, graduating with a BFA in 2019. Since then, Desir’s had an impressive trajectory, with solo exhibitions at esteemed galleries such as François Ghebaly in Los Angeles, Jupiter Contemporary in Miami, and 47 Canal in New York, the latter of which the young artist formerly worked for as an art handler, joining its roster after a unique painting on a steel plate caught their eye during a studio visit.

Desir’s practice spans sculpture, assemblage, and painting, mediums he animates with a spiritual lifeblood. Motifs of colonial histories emerge in a manner that mimics the act of faith. Desir worships through a lathe, so to speak, working wood, bronze, and metal to the point that they become representative of the resilience of the human condition, stripped down to base viscerality.

I met Desir in 2018 at a friend’s punk show, and two years later, my dear friend L.A. and I were interviewing him at his first solo exhibition, Swing Low, Sweet Chariot. We were all new, young, and excitable. Desir produced a lot of that show at his Cooper Union studio; today, he has his own. Over the past five years, both our careers have retained that earnest and welcomingly green attitude, wildness gradually refining into measured quirk.

Desir’s body of work frequently draws from biblical narratives, using them as a lens through which to examine diasporic struggles and endurance. His sculptures, such as Ode to Job (2021), embody both suffering and faith, depicting figures marked by hardship yet unwavering in their conviction. Strength in vulnerability, beauty in distress—these are the ideological containers that characterize much of his artistic voice. Most recently, Desir showcased his work at Frieze Los Angeles, further cementing his presence in the global art market. His latest pieces delve into ideas of labor, productivity, and the body as a machine, reflecting on how systems shape human existence. As he prepares for another solo show at 47 Canal, he embraces an “album mode” mentality—moving beyond the exhibition space as a platform for experimentation, into a deeper and more specific vision.

Raw wood for Desir’s carvings in his Los Angeles studio.

Maya Kotomori: The last time I interviewed you was in 2020. Swing Low, Sweet Chariot really stuck with me, especially the way you used wood. What do you think has changed the most, or stayed the same, between your work then and now?

Emmanuel L. Desir: That’s a great question. I’d say scale has changed, and my understanding of things has deepened. I’ve gotten older and I think that reflects in the work. There’s also my understanding of the art market—what it means to sell art while staying true to what I want to express. People mainly know me as a sculptor, but I love painting too. Ideally, I’d paint when I’m on my chill shit and do bronze and wood carving when I’m turned up. But when deadlines come into play, it shifts from being just about expression to completing something on time.

When I was making art at Cooper [Union], I was thinking, ‘Oh, I’m about to make a bunch of work and it’s going to help me get into Yale.’ That was my goal at the time. I didn’t end up getting in, but I had all this work afterwards. The gallery [47 Canal], that I used to be an art handler at, came to my studio junior year. They liked the work. Then they came to my thesis show senior year, and I was invited to do a solo show with them that summer.

MK: Now you’re an artist on their roster, and you moved to LA.

ED: Yes, I moved to LA that summer because it was COVID. I did my first show at 47 Canal. It went well, so I was like, ‘Let me go somewhere else with my life.’ And I didn’t want to be in New York for COVID during the winter. I felt like that would have left me feeling depressed. I feel like it worked, but I do miss New York every day, and I’m always thinking about moving back. I go back and forth, establishing myself in both cities because they both have different things to offer, coming up in the art world.

“Bronze has this beautiful dichotomy: It’s used to preserve victors in the great wars of history, but… also represents third place in a race or a competition. The metal represents being at the top and the bottom of the totem pole.”

MK: What would you say is the biggest difference between the LA art world and the New York art world?

ED: The New York art world is kind of wild because everybody is somewhat involved in it, and in LA it’s really cliquey, which is valuable too. LA champions LA artists and New York champions, like, the world. Even in painting, you see LA artists reference LA culture more, and New York painters reference their own interpersonal worlds. You can see it in the materials too. There are a lot more ceramicists in LA than New York; a lot more conceptual artists in New York than LA. It can be a lot more art theory-based in New York.

That can be dope. But in the same breath, in LA, I feel like a lot of people are making things that speak to the viewer’s colloquial terms, not super heady and academic.

I’ve never lived anywhere else besides New York. For college, a lot of people go out of state, but Cooper [Union] was in my city and, looking back, I feel like it was God’s plan for me to move now. I didn’t get that crazy college experience. But if I was somewhere else, I don’t think I would be where I am today. Shout out New York City!

My freshman year I was broke as hell. I printed out, like, 30 resumés and went around to every gallery downtown, like, ‘You need art handlers?’ 47 Canal called me back, that’s how it started. You know the business, though—you want to make the work that you want to make, but you also want to make sure you’re respectful of current events. Let’s say you make a piece two years ago that has an airplane in it, and then yesterday, there’s mad airplanes everywhere. Now all of a sudden, nobody wants to put airplanes in their work because it’s a sensitive topic at that moment. That’s the game, too. I’m not saying it’s wrong, it’s just something that I had to understand as an artist.

MK: Does that have anything to do with why you’ve leaned more into sculpture than painting? I also have to ask about your use of bronze, because it’s so captivating—what does that material mean to you?

ED: I have always painted, but sculpture is more complex and 3D at this point in my practice. I think I’m in a sculptural mode at this point in life. I feel like people who paint, paint, and the industry just wants them to stick to that one thing—because there’s a clear market around painting. The fact that I can do sculpture makes people feel like, ‘Yo, you should just focus on that.’ If I did a painting show, though… We’ll see.

With the sculpture, though, bronze has this beautiful dichotomy: It’s used to preserve victors in the great wars of history, but in the same breath, it also represents third place in a race or a competition. The metal represents being at the top and the bottom of the totem pole.

MK: This feels like a metaphor for Blackness.

ED: Yes, and all children of God who suffer at the hands of man. It feels like an overarching concept that resonates with Black groups all over the world, all oppressed peoples. Working in bronze has allowed me to be more intentional. I was learning how to work with it in school, and I liked how many qualities it reveals. I feel like a lot of my work tries to be real and speak to a truth. Bronze allows me to speak to my energy source and uplift the voices of God’s children and express how we inspire the world, as if we are the salt of the earth. That’s something in the Bible, too—the ‘salt of the earth’ being a phrase to speak to the children of God. Salt is a preservative, and it is still a flavor. And Black people have been preserving and inspiring the world since the beginning of time.

MK: The dregs of oppression. I love it. The idea of religious artifact is a huge throughline in your work. What is your personal relationship to God?

“It’s a delusion to think anything is just one way.”

ED: You know, I’m not perfect. I try to live as a servant of God, promoting righteousness and positivity. As an artist, my contribution is as a thinker and an inventor who personifies the beauty in our people as well as the hardship and the evils of being human. We’re not angels and we’re not demons, either. My work speaks to the complexities within Blackness—how we’re not monolithic, how we have to prove ourselves even among our own. I want my work to capture that intelligence and nuance, in every little detail and motif.

MK: What makes bronze the most limitless medium for you?

ED: Because of what you can do with it. It can be light, it can be heavy. You can carve it, weld it, pour it, patina it—you can even manipulate weight distribution to defy gravity. It’s still mysterious to me. Wood, I’ve mastered. Bronze keeps me inspired.

I’m embracing the repetitive motifs in the work rather than trying to create completely separate stuff. One of my teachers at Cooper, [Glenn Goldberg], once told me: ‘You can either date around with an idea or you can marry it.’ And now, I really fuck with where I’m at. I gotta expand it and talk about life through it—because life is so faceted.

MK: There was this show in 2023 that I stumbled into—it was one of the first days of me walking around after I had ACL surgery. It just so happened to be your show, Ashes of Zion. I remember this figurative sculpture [A Stiff Necked People (2023)], and it was positioned right in front of this large-scale painting of this idyllic, righteous scene of a pyramid-like thing—almost like it was studying it, like an audience-member. I already felt like I had this new perspective, with that being the first day I could walk around for the past three months. Looking at those two works added another layer to my experience. Was that an intentional choice, to put the sculpture in front of the painting like that?

ED: I feel like the science behind madness is universal, but then there’s always bridges between ideas that audiences will see as nuance, like the sculpture and the painting. In terms of the thought process and the motifs that are expressed by the medium, that’s usually something I look at in retrospect. I don’t finish a work and think to myself, ‘Oh, there’s a similarity here, let me move this so it looks like this.’ I really love when artists have a consistent theme and use the exhibition as a mixtape, because you can get so much range versus an album, which is more refined.

MK: Lil Wayne Da Drought 2 is a perfect example of this.

ED: Exactly! But in the same breath, I’m personally trying to get into my album mode for my show coming up.

MK: Tell me about that!

ED: I feel like I finally got all the parts I want: I have the understanding of the idea, and the infrastructure to bring it to life, and now it’s just a matter of completing the objective. The question is no longer, ‘What is the objective?’ but, ‘How can I complete the objective?’ It feels like leveling up.

MK: Speaking of leveling up, how was LA Frieze? What were your standout moments at the booth?

ED: I heard Lizzo pulled up. Jada Pinkett Smith and Willow came to the booth. It was mad lit. I was all over the place, seeing a lot of things. I got some good write-ups, but when I was in it, I wasn’t overly fulfilled or excited. I was mostly trying to help people get in, answering questions about the work. It felt good, though. That’s what you want as an artist. I’ve done Art Basel Miami, I’ve done Frieze London, Felix [in Los Angeles], Kiaf Seoul. Fairs are cool: There’s a bunch of galleries in one spot, so people are going to see the work, meet new artists. And everyone gets fly to go do that—I like that people dress up for the occasion. Fairs are a different pace than just being at a gallery. They’re almost like a carnival. Everyone congregates in the name of art, seeing old work, new work, young artists, established artists.

MK: What was your favorite conversation?

ED: I went to the World Series of Art Poker event and I met A$AP Bari. I saw bro during the event, and then my man Eddie Cruz—he does the Undefeated sneaker shop and [gambling service] Casinola—came up and introduced me officially. I showed him my work and he really liked it. Like, he said it was fireeeee. So that was the sickest moment. I just told him, ‘I really appreciate that brodie.’

MK: Potential for collaboration…?

ED: Only God knows. I want to do fashion collabs with brands like Martine Rose, Wales Bonner, Supreme.

MK: Respect. You also have an upcoming show with 47 Canal on May 8. What should audiences expect to see?

ED: Like I said, I’m in album mode, trying to produce around this idea of the body being a machine—how that operates in the world through social standings, what jobs you may do, collecting all those facets of productivity that create our society. I’m thinking a lot about what it looks like to ‘function.’ We got sculptures. We got paintings. I’d say similar themes, but I’m really thinking about functionality and implied functionality. A lot of the work has to do with perception versus reality. I want to take it further scale-wise, trying new stuff, working with new tools, new designs, new characters.

MK: The body as a machine—do you mean, like, high performance, the ability to function?

ED: Yeah. A machine has a motor. Thank God for the motor—it’s made our lives easier. That’s a motif that’s been coming into the work more. I’ve always dealt with personifying objects, making the being part of the object. Some people’s last names are Shoemaker—that’s a literal example of what I mean. People become their roles in order to survive, and that’s passed down generations. That’s dictating the decisions I’m making, the union of bodies and objects, biology, life, spirituality. Sometimes [my sculptures] look agonized, sometimes beautiful. It’s a delusion to think anything is just one way.

I’m chipping at not just Blackness, but the position and purpose we, as children of God, have on Earth. Our lives are so wrapped around systems we can’t live without. Exploring that, making new connections—formally, physically, materially. I’m working with different metals, and that’s even in the Bible. The potter’s clay, the mixing of materials, especially bronze. I can work on it soft, I can work on it solid. It feels like building something. It’s fun. Stay tuned—I hope I do some cool shit.