The Unerasable Image

Oluremi C. Onabanjo, the curator of the forthcoming Ideas of Africa: Portraiture and the Political Imagination at the MoMA, discusses the political resonances and imaginative possibilities of portraiture.

This story appears in Justsmile Issue 7, What We Carry Forward.

Text Jessica Lynne

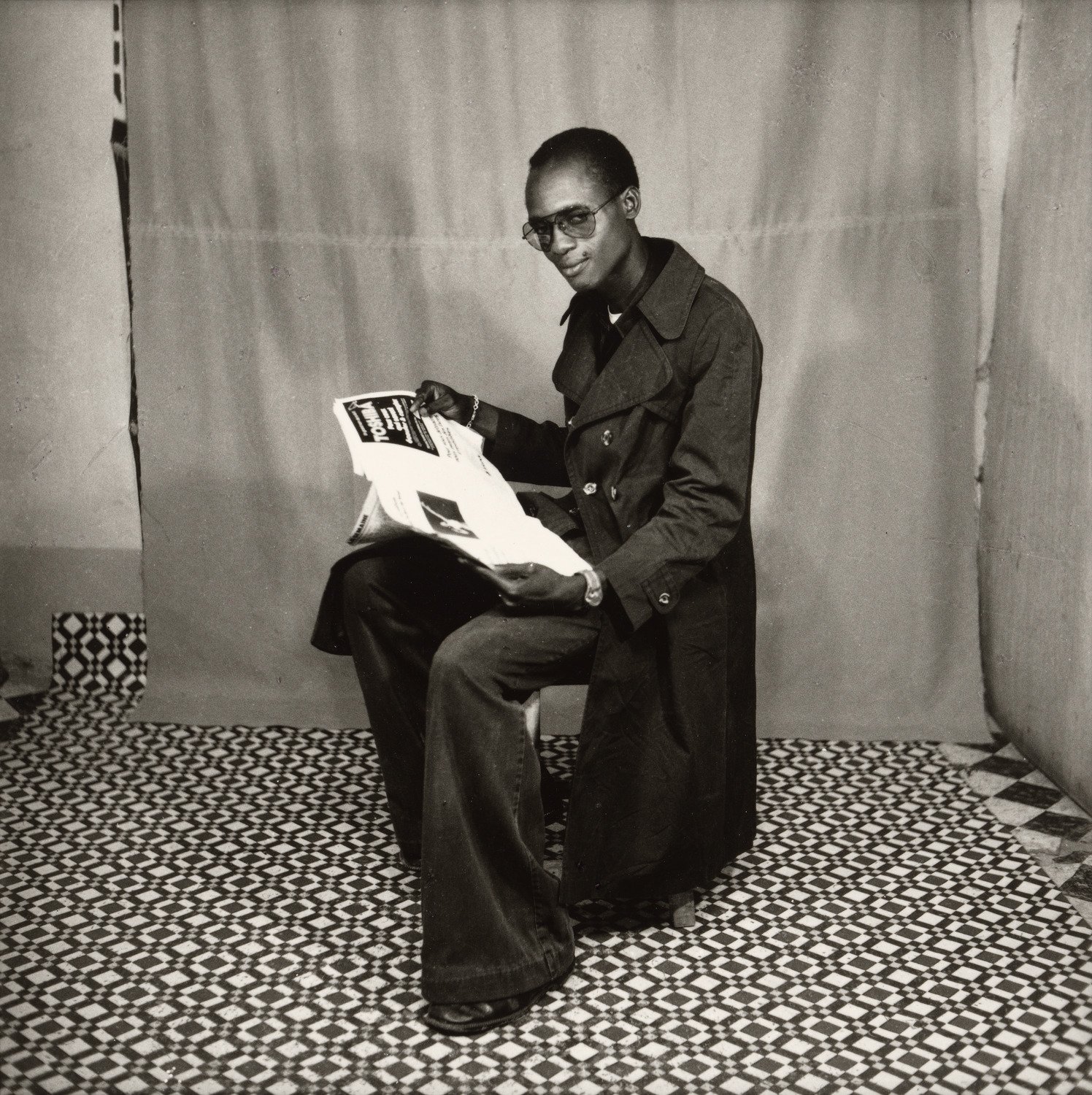

Sanlé Sory. L’Intellectuel (The Intellectual). 1970-85. Gelatin silver print. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Committee on Photography Fund. © 2025 Sanlé Sory. Courtesy of the artist and Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

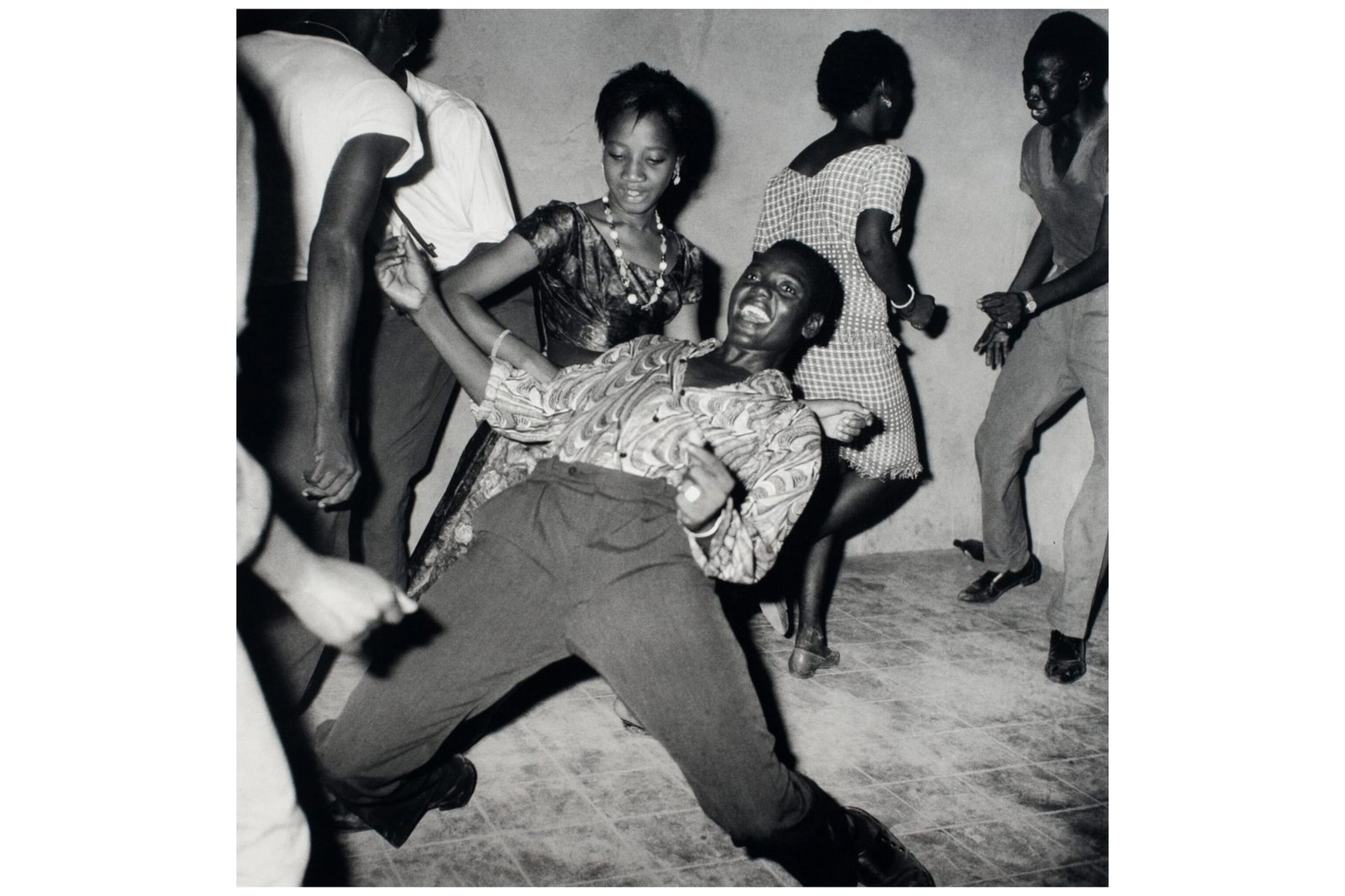

In Malick Sidibé’s photograph Regardez-moi! (Look at Me!), from 1962, a young man appears to be having what I can only describe as the time of his life. Surrounded by others—dancing, sweating, feeling intensely whatever rhythm calls out —he leans back at the waist, knees turned inward for support, with his shoulders firm and arms out in front of him. It looks, at first glance, as if there is a bar he is steadying himself to waddle beneath, but there is none, only the clear and certain smile he wears spread on his face. A young woman stands beside him, glancing at his movement, dazzling in her own right, and I can almost hear the sounds of Bamako at night, a capital city alive two years into independence. I can almost hear an affective language as it comes to life in Sidibé’s image, in a moment of revised social expectations and political contours.

Sidibé and his enlivening images of Bamako residents during the 1960s and 70s are part of a wider cartography of portraiture from the African continent mapped in the exhibition Ideas of Africa: Portraiture and Political Imagination, which opens December 14 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Organized by Oluremi C. Onabanjo, MoMA’s Peter Schub Curator of Photography, the show proposes a reconsideration of the political resonances of portraiture as aesthetic methodology, inviting viewers to look closely at transnational, self-referential gestures of self-determination throughout Africa as new sociopolitical worlds were being constituted. This process was as rigorous (and defiant) as it was creative.

Kwame Brathwaite. Untitled (Sikolo with Carolee Prince Designs). 1964–68. Inkjet print, printed 2018. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Committee on Photography Fund. © 2025 Kwame Brathwaite

Onabanjo herself is precise, deliberate, and intellectually exhilarating. We meet for our interview inside the quiet study room of her department, but not before she proudly walks me past a series of portraits taken by the South African photographer Zanele Muholi, installed on the second floor of the museum by her colleague Chiara M. Mannarino. Onabanjo pauses to admire them, not as though she is seeing them for the first time, but as if she is still learning something new about each image’s texture. As we settle into our conversation, both dressed in the art world’s favorite color—black—I realize that, as demanding the position of curator is, particularly at one of the world’s most storied institutions, it is also a role that requires an endless sense of wonder, an indefatigable ability to understand close-looking as praxis. Few people embody this the way Onabanjo does.

Onabanjo’s curatorial commitments encourage an embrace of nonlinear African diasporic timelines and cultural contexts. This is evidenced in her editing of the publication Last Day in Lagos, on Marilyn Nance’s FESTAC 77 photographs, and other exhibitions such as Projects, which rearticulated the profundity of Ming Smith’s decades-long practice. Through Onabanjo’s grappling with the photographic image, she reminds us to position ourselves as close to it as we can—and thereby as close to history as we can—in order to perceive the multiplicities of narratives that might exist within a single frame.

Here, we speak about the themes and origins of Ideas of Africa, and what remains at stake for her as she takes up the task of exhibition-making within a wider lineage of mentors, artists, and peers.

Malick Sidibé. Regardez-moi! (Look at Me!). 1962. Gelatin silver print, printed 2003. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Jean Pigozzi. © 2025 Malick Sidibé. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Jessica Lynne: You foregrounded this exhibition conceptually in the scholarship of V.Y. Mudimbe and his book The Idea of Africa. How did you come to choose that?

Oluremi C. Onabanjo: When I was first assigned the exhibition, it was around the 30th anniversary of The Idea of Africa, and I was thinking about the impact of Mudimbe’s philosophical formations in the 90s on a cadre of thinkers across many disciplines, be they musicians, art historians, cultural theorists, or curators. I was wondering what it might look like to bring his thoughts to bear on a new generation of issues around connection, identity, and the crisis on both fronts. I found it important, as I was re-reading the book, to shift the stakes of conversation around portraiture on the continent from a nexus through which they have been extremely well-documented—such as the conversation around identity—towards something that was about imagination. I found his extremely thorough, granular, theoretical formations a nice generative space to think through adjacent issues.

Mudimbe has made many contributions, one of which is the notion of the colonial library. If one is thinking, through reading, of conceptual formation as one way of making interventions, how can another generation build off those critical formations and perhaps generate other pathways? This is really an exhibition that is trying to make the case for why it’s important to continue looking at work made during the 20th century, but also demonstrate how artists show us pathways for moving forward and beyond what we already have seen and know.

Silvia Rosi. Disintegrata di profilo (Disintegrated in Profile). 2024. Inkjet print. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Carl Jacobs Fund. © 2025 Silvia Rosi

‘I don’t think that photography can ever be exhausted.’

JL: As you note in your essay “Photographic Portraits, Political Imaginations,” the abundance and presence of the discourse of representation, as it relates, in particular, to Black and African photographers, is with us consistently and continually. This is not to say that’s not an important effort, but that the project of representation is one that lives at a singular register. Your show argues against that simplicity. What’s at stake for you in that argument?

OCO: What’s at stake for me is why is photography still important—what does it mean not just for an aesthetic life, but also for a political life, a civic life, a social life? If photography, especially photographic portraits of people, only functions on the register of representation, then one might say it has exhausted itself, and I don’t think that photography can ever be exhausted. The introduction of additional lenses, the introduction of different angles of interpretation, is important right now because it demonstrates the continued relevance of looking at photography.

If one reads the photographic image, especially of another person, only through the means of documentation of a specific self, it assumes that that self is stable and that the photographic image is stable. That closes us off from all the potential resonances of the image. I wholeheartedly believe in looking and then looking again—looking differently, looking at an angle, looking with someone else, hearing what that person sees. So, what’s at stake for me is not only why we keep looking at photography right now—especially in a moment where images surround us and it’s important for us to know how to look—but also for a recognition that artists continue to build off one another. There’s a way of looking, or a way of knowing, that is really particular to the way that photographers look and make, and to the way that we can learn in space.

‘This will be the first exhibition that deals with the history of photographic portraiture on the African continent at this institution (MoMA).’

JL: To this end, knowing that each artist speaks to a set of revised or new possibilities—as is the refrain across your essay—were you surprised by any of the imaginative presences of the photographers in the show?

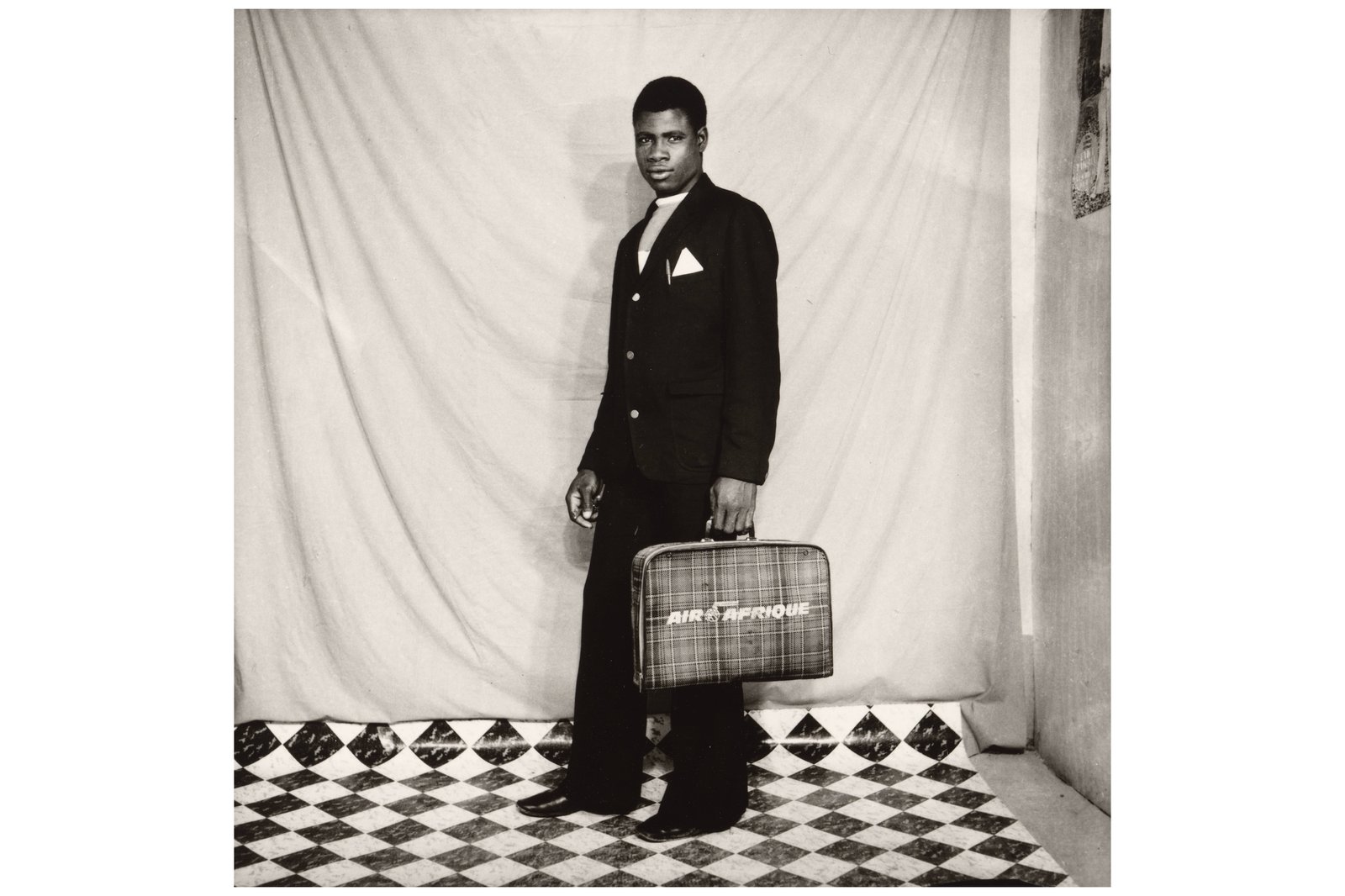

OCO: I was surprised by Sanlé Sory, particularly in the way that photography functioned in his social universe. When I was working on the show, I already knew a bit about how Malian photographers such as Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé functioned in relation to shifting attitudes around the state and the self, and how forms of subjectivity were expressed and received and circulated. For example, we have a beautiful set of what one can playfully call Malick Sidibé’s chemises, which are these contact prints on pastel cardstock that were literally displayed in his studio for people to come and see. These were pictures he had made the night before at parties, which they could then take home. I knew about that level of sociality around the image, but I didn’t know about Sanlé Sory’s marshaling of parties. He would set up these bal poussières in the rural flats of the Kou Valley, adjacent to Bobo-Dioulasso in Burkina Faso, then Upper Volta. He was not only documenting, but setting up, serving as an emcee, displaying the images in his Volta Photo studio. He was truly an enterprising, active agent in these sites of nightlife and youth culture. I enjoyed learning that.

I knew that transnationalism was not transatlantic. To be transnational on the continent is to think about how, for example, Jean Depara will be listening to music that spans Africa. That Sanlé Sory’s backdrops, in what is now Burkina Faso, were constructed by Ghanaian seamstresses and fabric workers. The fact that J.D. ’Okhai Ojeikere was making an index of the postcolonial self as Nigeria was coming into itself. There’s a sense of transnationalism that’s really important to keep in mind when it comes to the African continent and, of course, that resonates transatlantically, but it’s also happening on the continent. That was really important for me: to emphasize that specificity gives us a sense of flux, flow, and movement that then constructs a larger idea, rather than the idea being something that is constructed from the outside, and therefore becomes monolithic.

JL: It’s not necessarily thinking against diaspora, but articulating something within the political boundaries of what we know as the African continent.

OCO: The diaspora functions in all these different ways. There is not just one narrative of diaspora. Diaspora has within it all of these various possibilities and pathways. What I believe ardently and argue for in this show is that the photographic medium and its relationship to portraiture gives us a very specific and porous, generative way of discerning those different specificities.

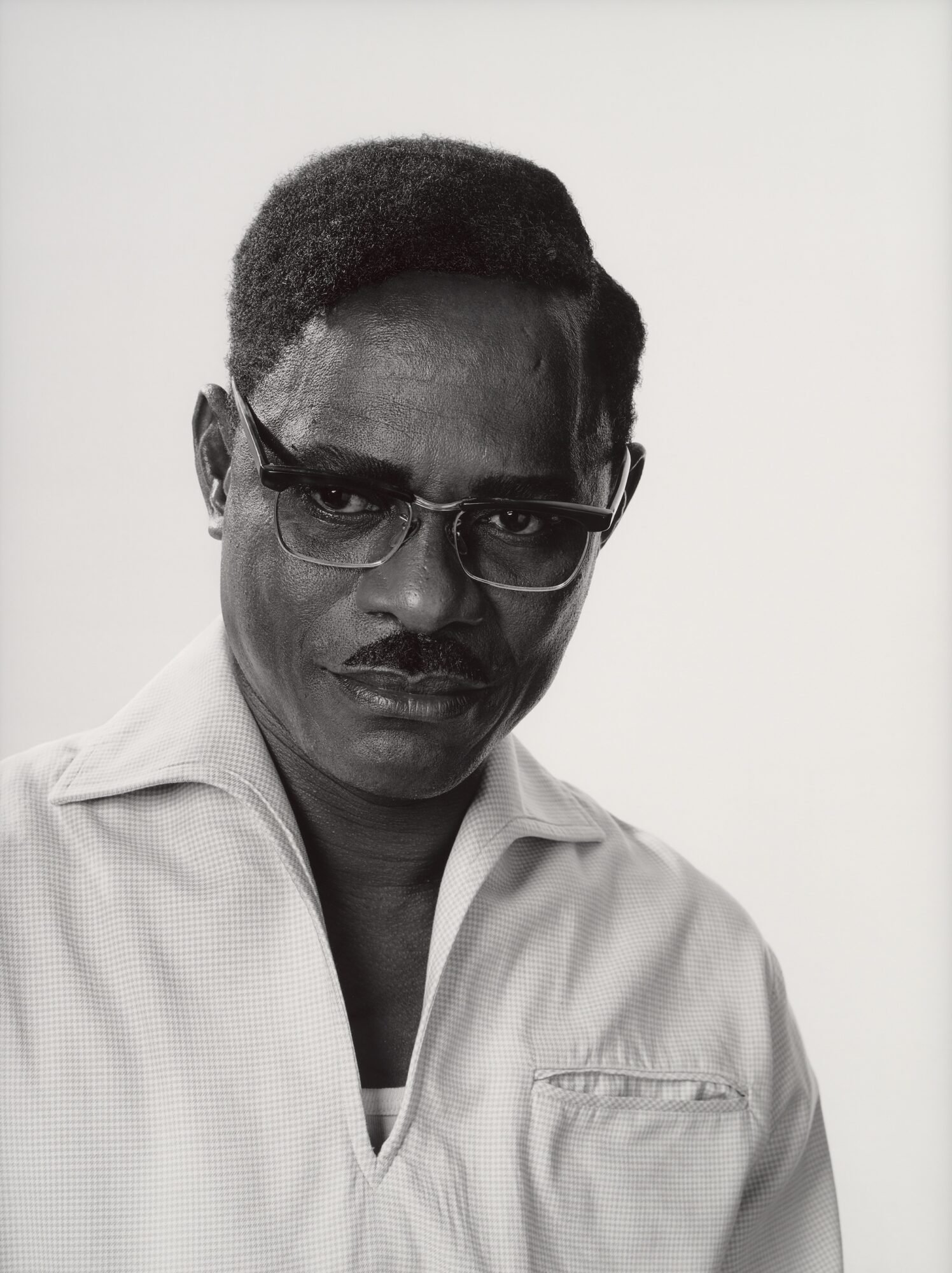

Samuel Fosso. Untitled from the series African Spirits. 2008. Gelatin silver print. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Family of Man Fund. © 2025 Samuel Fosso

JL: It strikes me that this show and your scholarship, broadly, is trying to present a simultaneity, a different kind of timeline. That is an urgent project, and one that, to the point about representation, gets subsumed in a very one-dimensional narrative.

OCO: A curator learns from a generation of extremely large, ambitious arguments. What I find to be methodologically useful at this current moment—and as a beneficiary of those big, ambitious, blockbuster, tectonic stakes in the ground—is that we can also work on a different register. I’m interested in the nimble narrative. I’m interested in the narrative that stays with you. I’m interested in the image that you can’t get out of your head, that keeps coming back again and again. I feel they’re not at odds with one another. In fact, I can make this kind of argument because of shows which have done that and because of books that have made those claims. But in order for us to continue generating and making the case for why looking at photography is relevant, we need to think on different registers.

‘A curator learns from a generation of extremely large, ambitious arguments.’

JL: What, then, does it mean to have a show such as Ideas of Africa live within the museum’s wider relationship to photography?

OCO: I take it as an invitation with deep responsibility, because this will be the first exhibition that deals with the history of photographic portraiture on the African continent at this institution. Hopefully, it is not the last. I try to make the opportunity count as many times as it can. That means, in making this exhibition, it’s not only about the exhibition. It’s about public programming a year before the exhibition starts. That’s both within the context of our study center, which you and I are sitting in, but also a public program in our Bartos Theater that gives people just a starting point for why these ideas matter.

We’re very fortunate. This show has a really long runtime. We’re hoping to have evening walk-throughs twice a month and programs collaboratively with our colleagues in film. We’re going to have a doubleheader with the Modern Monday film program in March where we’re going to think through diaspora from different positions. I take opportunities like this as invitations to embrace the spirit of an institution that, at its core, is committed to experimentation, to being a home for artists and their ideas, and to thinking about the art of our time. I will wring everything I can out of that opportunity so that as many people as possible can benefit from it, engage with it, tussle with it, fight with the ideas, and respond to it.

Sanlé Sory. Le Voyageur (The Traveler). 1970–85. Gelatin silver print. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Committee on Photography Fund. © 2025 Sanlé Sory. Courtesy of the artist and Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

JL: Can you name and situate yourself, and this show, within a lineage of some of those tectonic projects you referenced? I know the late Koyo Kouoh, for example, is someone deeply important to you on a personal and professional level.

OCO: It’s important to note that this is a show about the history of photography on the African continent and the diaspora that’s happening in New York. The show will not travel; it will only be here at 53rd Street. By being here at 53rd Street, it is immediately put in relation to other shows with similar subject matter that have happened in the city. One cannot think about that without thinking of the late Okwui Enwezor, whose exhibition In/sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present was at the Guggenheim in 1996. Then his exhibition Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography was at the International Center for Photography in 2006. The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945-1994 started abroad, but came to MoMA PS1 in 2002. It’s also in dialogue with shows this institution has done: two on David Goldblatt, the first in the 90s, organized by Susan Kismaric. There is also Africa Explores, organized by Susan Vogel and presented at the New Museum and the Museum for African Art, now called the Africa Center.

One could also think about the contributions of the late Bisi Silva, another mentor of mine, who founded the Center for Contemporary Art Lagos in 2007 and was curator of J.D. ’Okhai Ojeikere’s retrospective and book. She also organized Telling Time, the tenth edition of Bamako Encounters. And, exactly as you mentioned, the late Koyo Kouoh, who I worked with on the Hamburg Triennial of Photography and who was an unbelievable institution builder and exhibition maker. One benefits also from the positions of someone like Antawan Byrd, as well as Simon Njami in Paris. I mean, the list is extensive and full. When I mentioned the ability to be really specific in claims and methodological approaches, it’s because, thankfully, I’m not the first one who’s done this.

As you’ll note, the catalog of the book is dedicated to the memory of both Felicia Abban and Koyo Kouoh. Recognizing who is no longer with us in flesh but stays with us in spirit is really important. We also have a little reading room embedded within the exhibition that includes a number of the catalogs for those shows that I mentioned.

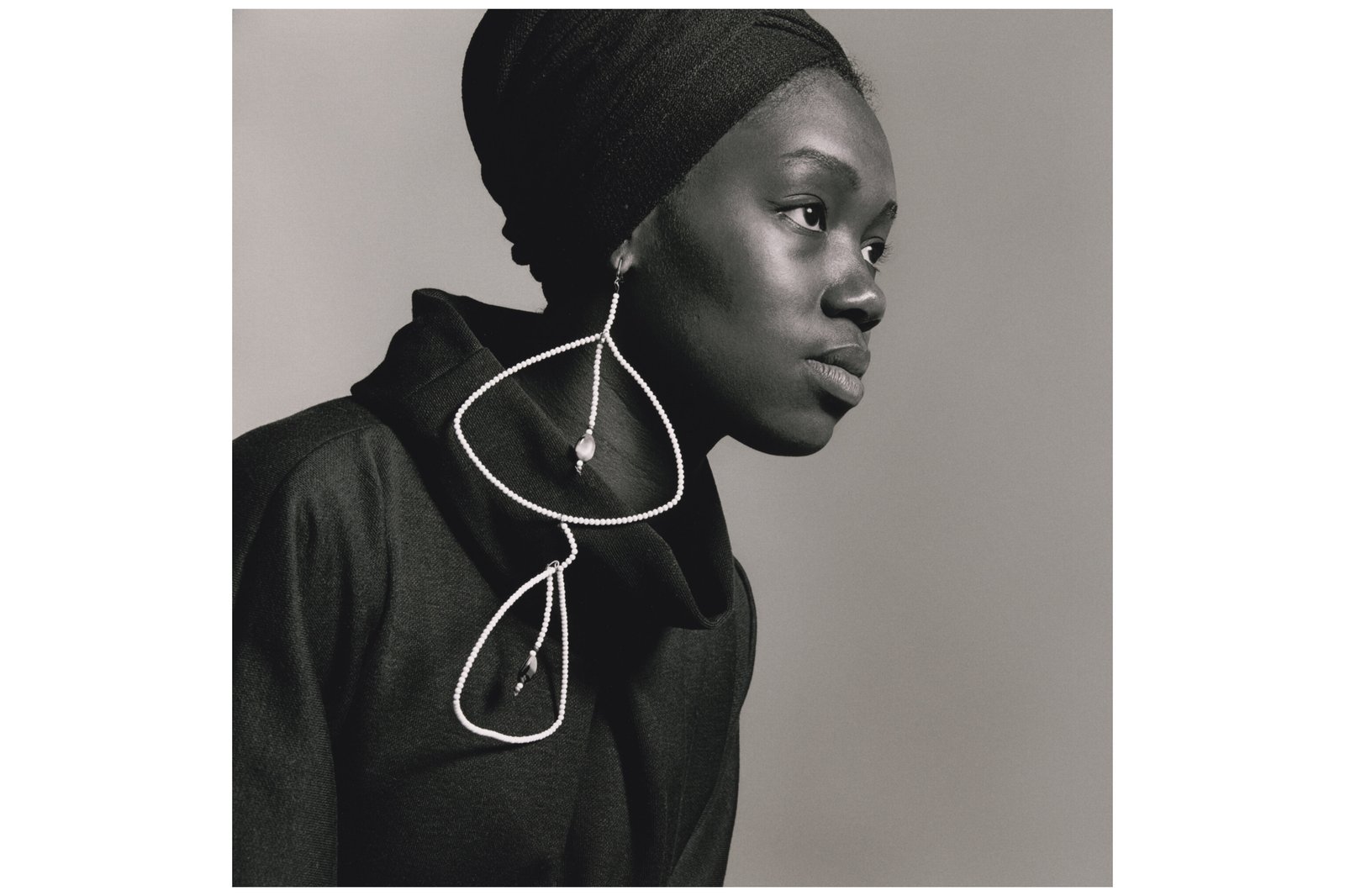

Kwame Brathwaite. Untitled (Nomsa with Earrings). 1964-68. Inkjet print, printed 2018. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Committee on Photography Fund. © 2025 Kwame Brathwaite

JL: One question that I bring to the show, particularly as it exists in New York City, the United States, and in North America, is how I might better understand the consequences of, and commitments to, practices of self-determination—knowing that aesthetics and wrestling with aesthetics are deeply implicated in such efforts, though not the totality. Are there other inquiries or troublings you hope people bring and leave with?

OCO: It’s funny. What you’ve modeled in that question is a little bit of what I’m hoping for people to experience, which is—I hope they don’t come to this exhibition thinking they’re going to be provided with answers. Rather, they’ll be provided with exciting, transfixing, enlivening approaches by a set of photographers who will help them ask more rigorous questions. My hope is that someone can maybe not think about politics and creativity as a binary, and recognize that the collision between the two does not substitute the actual change of one’s material existence and conditions. Art and life are entangled and, I think, photography in particular. If one comes out with some more precise questions about their surroundings, what they might mobilize in their daily life, and how that is related to a larger history, that will be my job well done.

This story appears in Justsmile Issue 7, available to order here.